Dada, while short-lived and enigmatic, proposes direction and accompanying attitudes for people working in the field of communication design. Designers paying attention to work from the Dada movement learn valuable lessons in repurposing existing materials and creating new works from the assembly of common objects into a form encompassing new meaning. A viewpoint attributed to the movement claims “artistic acts became matters of individual decision and selection” (Meggs, 256) and gives modern designers the freedom to pursue new forms created from obtained objects, without the rejection based on originality or lack of incomplete development.

The Dadaist idea of taking existing elements and transforming it into art paves the way for modern designers and artists to break out of traditional applications for materials and blur the boundaries of medium. Very few works from the Dada movement make use of the object in its original form and especially for its original purpose, which defies traditional art mediums. From the creation of the photomontage through collage (Meggs, 258) to the challenge of the limits of art irreversibly blurred by Marcel Duchamp’s ready-mades, the Dada movement gives today’s design discipline the tools to craft works that separate the medium from the artwork and use materials in interesting and new ways. Found objects in Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel show how a wooden stool and a wheel from a bicycle stop being individual objects when not only assembled in an artistic fashion but also while being changed through a thoughtful process. This new way of thinking about art as a process rather than an outcome also plays an essential part in the Dadaism influence.

Many Dada artists, such as Jean Arp believed that chance and choice of the artist characterized the Dada works. Contemporary communication designers employ this idea in a similar fashion. Objects collected through chance encounters are manipulated and compiled through the choices of the designer into a work that shows the objects as an intrinsic form rather than a purposeful item. “Art shouldn’t concern itself with ideal beauty, [...] but should heighten human awareness of the real by any means possible” (Filler, 2010). Giving designers this idea of playing with what is real and what is perceived allows new compositions of real objects to have a strong impact on the viewer.

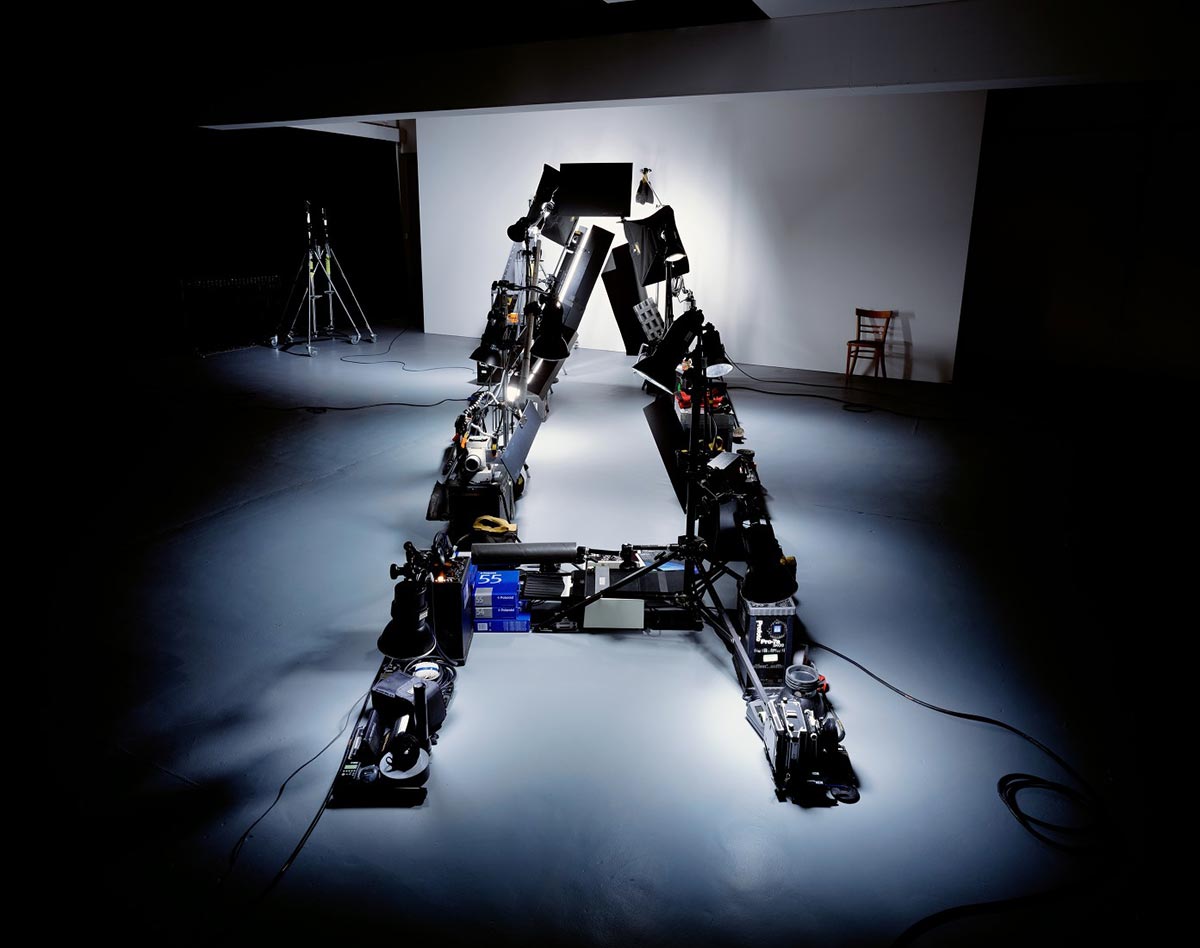

A prime example of the lessons of Dadaism comes from the work of Dan Tobin Smith and his series of typographic compositions called Alphabetical. Each work is composed from a plethora of repurposed objects including busts, rolls of tape, camera parts, shelves, boxes, cups, and containers, where the objects are composed in a dimensional space to create a perceived letter in front of the camera. Both Letter E (Figure 1) and Letter A (Figure 2) showcase how a single perspective on a random collection emphasize a personal and human meaning all on its own. This work employs the Dadaist idea of the disregard for the boundaries traditionally found between painting, sculpture, and image. Smith’s design work meets at the intersection between sculpture and image but maintains its connection to communication design through the expression of typographic elements. Smith claims, “I’ve always been interested in typography as a form of design, and I like the idea of photographically representing typography” (Abbink, 2010). Typography finds a new medium through careful choice of placement and random selection of material. The letterforms in Smith’s work are not confined to the medium of paper, but exist in a dimensional space until captured from the right vantage point.

Assemblage either by collage or a more sculptural composition relays the Dada practice of using found materials to create a new work, and Smith’s work revolves around this idea. The most interesting part of the compositions is the recognizable form of the letter existing from random and unrelated objects—something that again stems from Dadaism. The bits of equipment, lights, and figurines separately have no connection other than being a similar color and perhaps reflectivity (Figure 3).

But when singularities constitute a specific shape as intended by Smith, it communicates a whole new perspective on the relation of the objects. The letter is only formed through the composition taken in all at once. Without standing in the right place, or in this case taking the image from the right angle, the collection of forms reverts back to its disjointed nature. When viewed from an unintended perspective the objects become individual pieces and fail to form a collective message, but simultaneously reveals the process behind the design (Figure 4).

While the works of Dada artists can claim to be crafted from nonsensical objects and processes, their methodology and ideals still lead the way for more contemporary designers and artists. Communicating new ideas and forms through a pieced-together approach and using existing objects lets communication designers continue to engage and challenge the idea of which mediums apply to which disciplines, and what original compositions reveal about the separate pieces that power them.

See the project: Repurpose & Assemblage